Intentional Sourcing from Climate-Smart Forestry Operations

This “Choose Your Own Adventure” option entails identifying specific forestry operations that are practicing CSF – whether or not they are certified – and rewarding them through procurement. This can be done by establishing traceability and transparency for a given product, working up the supply chain to primary mills and analyzing working forests in the relevant supply areas. It can also be done by working forward from identified CSF forestry operations, engaging the supply chain actors needed to obtain a particular product for a project. Either way, this option relies on moving well beyond business-as-usual procurement.

In this procurement option, it is up to the project team to decide which forestry operations align with their goals and the CSWG definition of CSF. It is good practice to work with local or regional experts to identify CSF practitioners and their supply chain partners.

CSF is tailored to the ecological and social setting where it is practiced, but in general it improves outcomes across these three dimensions over the long term:

- Mitigation: Increasing storage of carbon in forest ecosystems and wood products, and reducing emissions from forest operations.

- Adaptation: Maintaining or building ecological integrity and diversity that are the basis for resistance and resilience as the climate continues to change.

- Equity: Addressing issues of equity and climate justice, improving community well-being and respecting the rights of Indigenous peoples. To be viable and sustainable, forestry must address how social and economic benefits and impacts are distributed among landowners, workers, and communities.

A fuller definition of CSF can be found here.

Landowner Types & Management Regimes

It is common for intentional sourcing to be focused on specific geographic areas, certain landowner types, and/or specific methods of forestry. The following are some examples of landowner types and management regimes that could represent CSF and be targeted for intentional sourcing of CSW:

- Non-Industrial Forest Lands: In general this could include Indigenous or tribal, non-profit organizations and land trusts, and family forest owners. Publicly owned forests such as US federal, state and Canadian crown lands could fall in this category, or they may be intensively managed in ways that should not be considered climate smart; therefore, they should be considered on a case-by-case basis. Government- and some tribally-managed lands can have a transparency advantage in that management plans may be publicly available.

- Restoration Forestry: Forests where management produces improvements in forest health, resilience, water quality, ecological integrity and diversity, etc. Examples include environmentally-responsible thinning to reduce wildfire risk, management that restores forests degraded by past intensive logging toward more natural conditions, and reforestation projects where the right trees are planted in the right places. Organizations exist across North America that practice restoration forestry and are likely to accommodate the intentional sourcing goals of project teams.

- Above-BAU Regulations: Some forests are governed by environmental or management regulations exceeding business-as-usual (BAU) practices at the legal floor. One example are the many millions of acres in the US that are governed by Habitat Conservation Plans, which entail a set of required commitments to protect federally listed species under the Endangered Species Act. HCPs commonly require additional conservation measures and management practices that are aligned with climate-smart forestry outcomes. Forests managed under an HCP are also highly likely to have inherent documentation requirements that can help satisfy project traceability and transparency objectives.

- Above-BAU Practices: Forests consistently managed using practices that exceed BAU regimes are likely to enhance climate, community, and ecological outcomes. This could include forestry operations that implement smaller clearcuts than allowed by regulation; extended harvest rotations (longer time periods between harvests, allowing trees to grow larger and sequester more carbon): increased green tree retention (leaving more live trees behind after harvest instead of removing everything), expanded riparian and wetland buffers (protected areas along waterways); habitat enhancements for fish and wildlife; etc. It could also include forests that have a positive Carbon Stock Change Factor such as third-party certified forest carbon projects that offer carbon offset credits tied to increased carbon storage over a regulatory baseline.

Sourcing Methods

Of course, with more specificity comes the need for more diligence. CSWG suggests two main methods for intentional sourcing of wood from CSF:

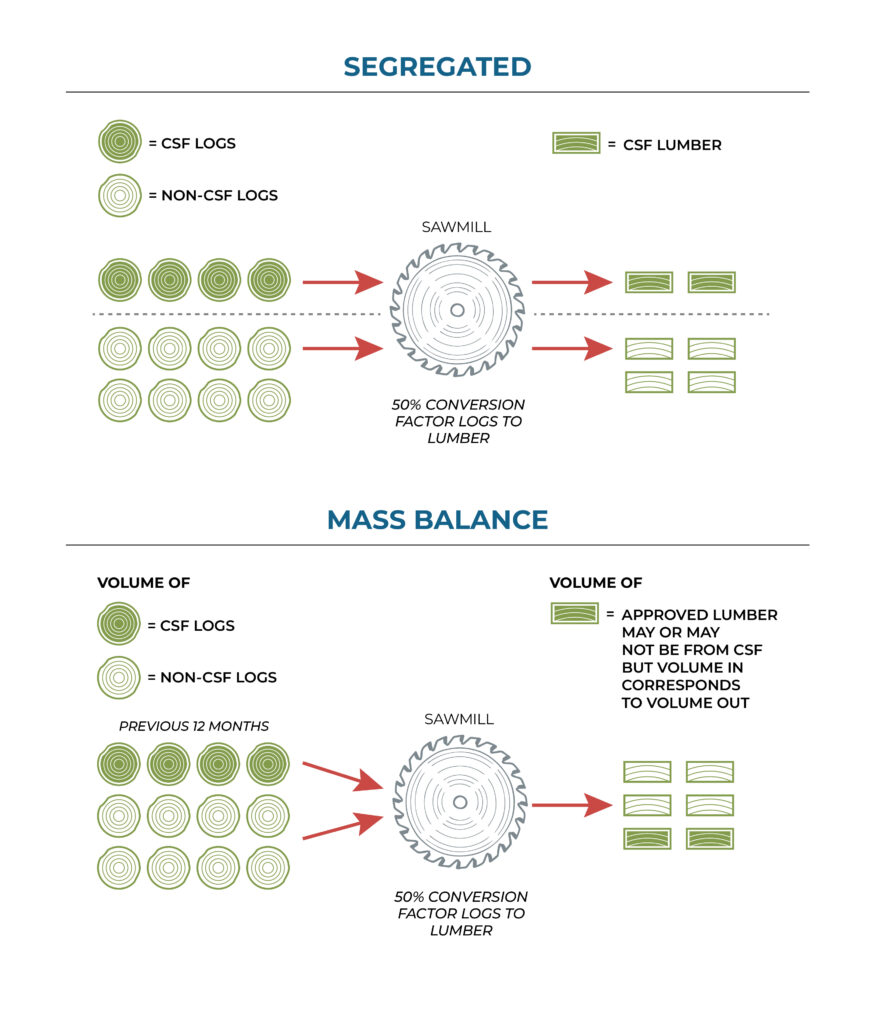

- Direct Sourcing & Segregation: To make a claim that wood from specific forests is literally built into the building, it means that wood must be tracked and segregated through stages in the supply chain where mixing is likely to occur, such as at log yards and mills. Sourcing wood directly from CSF operations requires segregating materials at different stages of manufacturing and tracking them through production runs and distribution. This requires enhanced logistics, so it takes the right partners, the right timing, the right size of job, financial incentives, and early engagement to make it work. More vertically-integrated or small-scale mills are generally better suited for segregation. In spite of its disadvantages, this method is often the only way to link wood products directly to their specific forests of origin.

- Mass Balance: Another, generally more practical way to reward landowners who practice CSF without relying on segregation is to take a mass balance system approach. This is a volume in/volume out method where a primary manufacturer is asked to provide documentation showing that they have procured enough logs from a given source over a fixed time period – e.g., 12 or 24 months – to “cover” the volume of product needed for a project. Greater certainty about the actual sources can be achieved by aiming for tighter production windows. This method can also be applied at the secondary manufacturing level. For example, if it is inefficient for a mass timber manufacturer to segregate material that has been approved by the project team either because it stems directly from a selected landowner via segregation at the sawmill level or because it has been supplied through a mass balance system at the sawmill, the mass timber manufacturer could provide purchase documents showing that they procured enough lumber from the sawmill in a designated time period to “cover” what is needed for them to produce the package. While using a mass balance approach breaks the direct connection between the product and the source forest, it still represents a basis for credible claims about what kinds of landowners and forestry practices the project supported. As noted above, many products certified under forest certification systems are manufactured using this method because it is more efficient and less costly than segregation. Although this approach is indirect in that you cannot claim where the actual wood in your project is coming from, it is still a way to reward CSF producers financially and sends a positive market signal about what clients and project teams value.

Figure 3

Why this is Climate Smart

The description above provides examples of indicators of potential climate-smart attributes that align with the CSWG’s definition of CSF, corresponding landowner types and implications for the level of traceability/transparency required to make credible claims. None of these indicators represents a stand-alone guarantee of climate-smartness. The inclusion of indicators like these in any procurement policies or specifications should include additional information and regional context. Examples may include describing why certain types of landowners are believed to produce improved climate[1], community, or biodiversity outcomes that exceed business-as-usual, or which forest management and conservation practices employed by timber producers are considered (e.g., extended harvest rotations, increased green tree retention, expanded riparian and wetland buffers, habitat enhancements for fish and wildlife, etc.).

Traceability & Transparency

Exercising this option requires traceability and transparency, as described in the first section of this guidance. Ideally, the exercise of this option will involve gathering data at the forest management unit (FMU) level (Level 3 disclosure). If working up the supply chain from an end product as opposed to forward from a CSF operation, then at minimum this option must incorporate traceability and transparency to the primary mill supply area (Level 1 disclosure).

Pros

- Direct Impact: With proper transparency and traceability, this pathway provides a direct method for supporting CSF practices. With full supply chain mapping and source forest disclosure, project teams should be able to point to specific positive outcomes that their projects have supported within specific forests.

- Market Transformation: By asking supply chains for the transparency and traceability needed for this option, project teams can transform the forest products industry in ways that differentiate forest practices, reward CSF, and make transparency requests more accessible for future projects.

Cons & Resolutions

- Added Complexity & Cost: This will generally be the most complicated option for sourcing CSW because identifying CSF operations, winning the cooperation of supply chain actors, and tracing wood products to their source can be a difficult, time-consuming and costly effort.

- Resolution: Seek the support of advisors and consultants familiar with wood supply chains and forest management practices in a particular region.